Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849)

In Our Gallery

Katsushika Hokusai's remarkable life resonates through time and across cultures.

In the annals of Ukiyo-e, no design is more iconic than “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa.”

This bold image of a gigantic, froth-tentacled wave enveloping both Mt. Fuji and crescent-shaped boats of huddled fishermen has burst out of the world of Japanese woodblock prints and into the mainstream of global culture. It appears on Swatch watches, in political ads, on record albums and yes, even on sexual devices. There are believed to be about 200 originals of them left on the planet. In March 2023, one sold in auction for $2.76 million, a record for Ukiyo-e. Meiji-era reprints can, absurdly, sell for as much as $5,000.

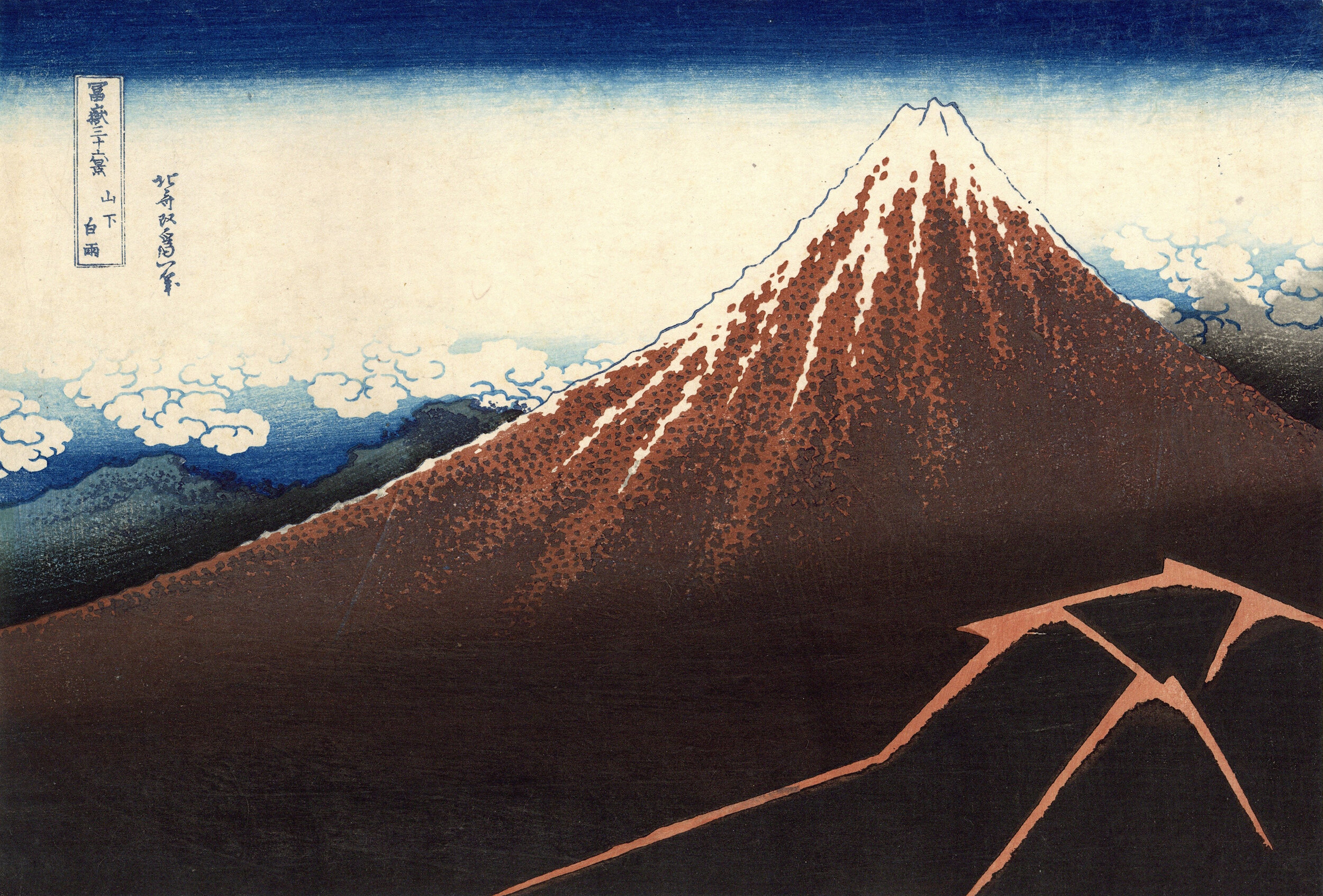

The fame of this undisputed masterpiece is a mixed blessing for lovers and collectors of Japanese woodblock prints. On the one hand, its notoriety brings attention to the form. But on the other it can take up all the oxygen in the room. New collectors chase it. But it can overshadow all the other arguably comparable masterworks by its creator – such as “Red Fuji” or “Rainstorm Beneath the Summit.”

And it can also overshadow its creator himself. And that would be a shame, for there are few characters more legendary, more prolific, more influential and more just all around interesting in the Ukiyo-e universe than Katsushika Hokusai.

Born in 1760 and living until 1849 – a long life in Edo times – he produced untold thousands of works, from intricate color prints to luxurious paintings to books upon books of drawings and sketches. His designs were boldly modern and instantly recognizable, in several cases deeply influencing Western art.

His voluminous sketchbooks are the clear forerunners of today’s manga comic books and Japanese animated movies. His lines were clever and precise. He was the subject of a major 2020 movie in Japan.

Alas, his personal life was a bit of a mess. Despite his fame, he often lived in squalor. Later in life, he referred to himself as “Old Man Mad About Drawing.”

Muneshige Narazaki, a scholar of Ukiyo-e, wrote:

Hokusai’s life spanned almost the whole of that golden age. His art progressed in gradual stages from the imitation of others to mature independence and the development of new forms, then went on to new heights while the form itself was lapsing into decadence, and finally survived to see itself become old-fashioned in its turn, and to be superseded.

He was born in Edo as Tokitaro Kawamura and was adopted by a mirror maker. Showing early promise, he studied with several Ukiyo-e greats, with varying levels of success. He’d changed his name repeatedly throughout his life. He began by doing designs for illustrated books.

His greatest series is undoubtably “36 Views of Mt. Fuji,” which was published by Yohachi from 1823 to 1832 and which includes “The Great Wave Off Kanazawa” as its centerpiece.

Many of the designs in this landmark series, which helped introduce the landscape genre to the thriving print marketplace, are exquisitely simple. It featured considerable use of Prussian Blue, just then introduced to Japan; the key blocks of the first 36 are in this pigment. I say “the first” because the series was so successful that 10 more were produced, and you can tell those designs because those key blocks are in black. So really, 46 Views of Mt. Fuji.

He followed up with three books of black-and-white only prints called “100 Views of Mount Fuji.” They are wonderful. Hokusai just couldn’t stop.

Until he did. Hokusai wanted to live to 100 years old but didn’t make it.

He had a daughter, Katsushika Oi, who worked as his assistant and turned out to be a talent in her own right. Some scholars have even attributed some of his works to her. And she had something in common with her more famous father: she was also the focus of a recent blockbuster movie in Japan.

Partial citation: Narazaki, Muneshige, Hokusai: Masterworks of Ukiyo-e (Kodansha; 1968); Marks, Andreas, Japanese Woodblock Prints, Artists, Publishers and Masterworks: 1680-1900 (Tuttle; 2010); Forrer, Matthi, Hokusai (Prestel; 2015)