Other Shin Hanga Artists (1912–1989)

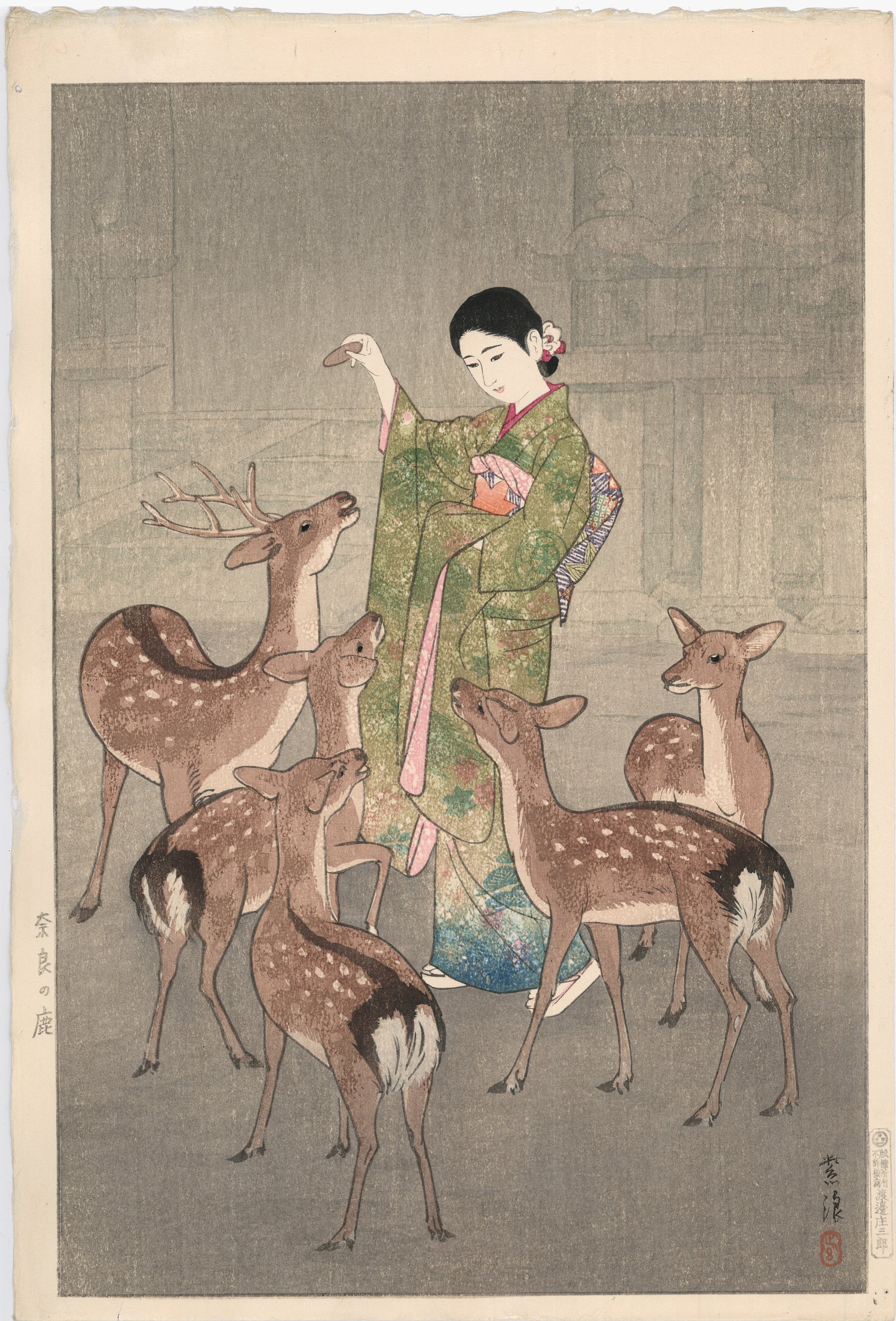

Ito Shinsui (1898-1972)

Born into poverty in 1898, Ito Shinsui was forced to take a job with the Tokyo Printing Co. when he was just 12. This bad luck turned out to be good luck for him, and for anyone who loves art and Japanese woodblock prints.

Naturally talented, but also a determined hard worker, he continued his education and studied Nihonga painting in the evenings. His talent was recognized at work, and he was moved to the company’s drawing section, where he became an illustrator – a skill he used throughout his life. But fine art exerted an irresistible pull. He became a student of the Ukiyoe painter Kaburagi Kiyokata and began winning prizes.

Like so many Shin Hanga artists, his connection with the great publisher Watanabe Shozaburo cemented his career and reputation. His first print for Watanabe was “Before the Mirror” in 1916. But here’s the twist: we know Shinsui as the great artist of beauties – bijin. But his first love actually was landscapes, and his wonderful, atmospheric and tonalist “Eight Views of Omi” remains a highpoint of early Shin Hanga landscape designs.

In fact, those early views were so well received that they prompted Hiroshi Yoshida and another Kiyotaka pupil, none other than Kawase Hasui, to pursue landscapes themselves. This, in turn, contributed to Shinsui’s switch to female portraits. Perhaps the landscape genre felt too crowded. But this became his true fame. His women were often caught at private moments, at the mirror or after the bath, gazing introspectively, deep in thought. Other times, they were out in the world, dressed elegantly, beautiful in the pouring rain or in the swirling snow. They are captured for all time in his greatest collections — the first and second, “Series of Modern Beauties" and "Twelve Images of Modern Beauties."

In the end, he and Watanabe executed 60 landscape prints and 100 portrait prints together, in addition to the occasional work Shinsui did for others. Throughout it all, he continued to paint. In his later years was acclaimed as a national treasure, his work embraced around the world. A long journey from the day that little 12-year-old boy started his first day in the noisy, dirty printing shop.

Koson Ohara (1877-1945)

Koson Ohara was famous as a master of kacho-e (bird-and-flower) designs. Throughout a prolific career, in which he created around 500 prints, he went by three different titles: Ohara Hoson, Ohara Shoson and Ohara Koson.

At first, he worked with publishers Akiyama Buemon (Kokkeido) and Matsuki Heikichi (Daikokuya), signing his work Koson. Starting around 1926, he became associated with the publisher Watanabe Shozaburo, and signed his work Shoson. He also worked with the publisher Kawaguchi, signing his works Hoson.

Through his association with Watanabe, Ohara's work was exhibited abroad, and his prints sold well, particularly in the United States.

Takahashi Shotei (1871-1945)

Takahashi Shotei may have once been the most well-known Japanese woodblock print artist in the world, even if the Westerners who bought stacks of his prints when they flooded Japan in the early part of the 20th Century didn’t know his name.

Watanabe Shozaburo hired him to design shinsaku-hanga (souvenir prints) to fulfill tourists’ demand for Ukiyoe-style woodblock landscape prints similar to those created in the past by masters of that genre, especially Hiroshige. These prints sold extremely well to this new audience, and were often in unusual sizes, to striking effect. (We wonder what Hiroshige would have thought of them.)

Shotei eventually took the name Hiroaki and produced hundreds of designs, but the blocks were destroyed in the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923. This is when Watanabe assigned him the unusual task of recreating his own works. He lived until 1945.

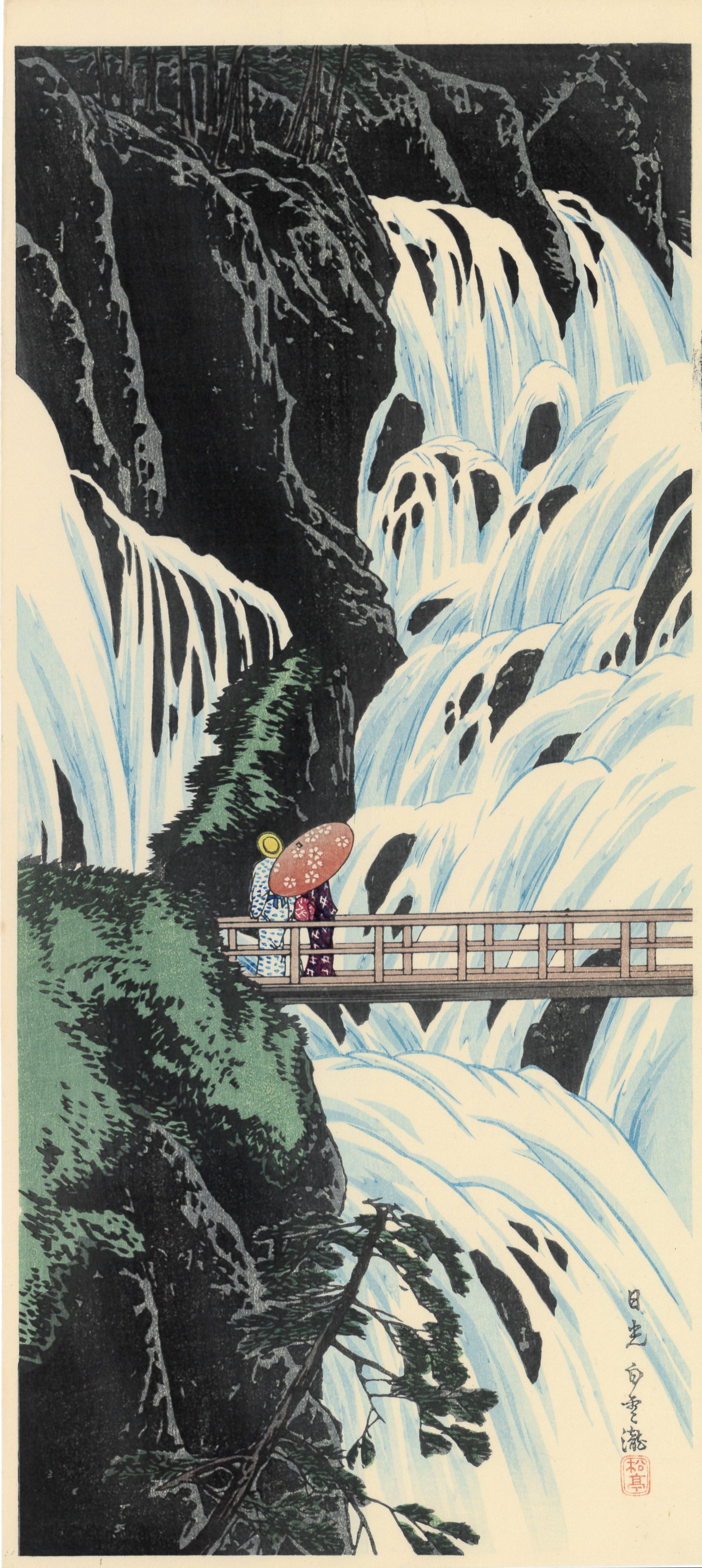

Kasamatsu Shiro (1898-1991)

Shiro Kasamatsu studied art with the painter Kaburagi Kiyokata beginning when he was very young, focusing at first on portraits of beautiful women. Watanabe Shozaburo saw his paintings in a show in 1919 and added him to his stable of Shin Hanga stars.

Shiro quickly gained renown for his landscapes of famous landmarks — always with a romantic sheen — and his scenes of traditional Japanese life. Later, up until 1960, he worked with the Kyoto publisher Unsodo, creating more than 100 designs. Hints of old Japan are juxtaposed with modernity in Shiro’s work — a tiny sushi stall in the foreground, for example, is dwarfed by modern, neon-lit buildings in the background, or, as in “Great Lantern at the Kannon Temple,” a man in a western fedora descends the steps from this most traditional of Japanese landmarks.

One of the last Shin Hanga designers, Shiro eventually experimented with sosaku hanga — creative prints — in which the artist carved and printed his own designs.

Tsuchiya Koitsu (1870-1949)

For Tsuchiya Koitsu, in a sense, life began at 60. That’s when he met Shozaburo Watanabe and started publishing designs with him. Decades earlier, he’d been a student of the legendary Ukiyoe master Kobayashi Kiyochika for 19 years — even living in his house — and was known for his dramatic triptyches portraying the Sino-Japanese War of the 1890s. In the end it was his work with Watanabe that gained him fame, and his particularly modern appreciation of water reflections and light effects.

Torii Kotondo (1900-1976)

Torii Kotondo started in the footsteps of his father, Torii Kiyotata IV, seventh head of the Torii school of Ukiyoe, focusing on prints of kabuki actors (yakusha-e), as well as working on stage design and production. In 1929 he succeed his father as head of the school. At the same time, he is known for his pictures of beautiful women (bjin), of which he produced 21.

Most of Kotondo's woodblock prints date from 1927 to 1933. But that was only a fraction of his life’s work. He was extremely prolific, producing paintings as well as prints and stage designs, and later in life became a university lecturer. Finally, he worked as an art consultant for television and films. What a journey: from Ukiyoe to moving pictures.

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi (1899-1948)

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi was born in Fukuoka, in northern Kyushu, but his designs have helped to define the Tokyo metropolis of the 1920s and early 1930s when Japan entered a unique and vibrant epoch, beginning with the Taishō Era (named like all such eras for the Emperor) and continuing into the early Showa period. One of the most visible signs of this rapid change in Japan were the “modern girls” – or Mogas – who paraded down the Ginza in flapper styles, who enjoyed cocktails and music, who strayed from the traditional roles of wife and mother and dutiful daughter-in-law.

Kiyoshi, who only made 13 prints, captured these snazzy young women in several famous designs, especially "Tipsy,” which shows one in a colorful polka dot dress with a marcel wave in her hair enjoying what appears to be an Aviation cocktail, a cherry floating happily within. It is among the most famous of all Shin Hanga works.

One reason for Kiyoshi’s limited print output was the fact that, for the most part, he was a painter. He won numerous awards for Japanese-style paintings before becoming interested in prints in the 1920s.

We’re lucky he did. For a fleeting instant, he captured a moment when the old and new felt balanced. In just a few years, fascism and darkness would wipe away the Mogas like they’d been a dream.

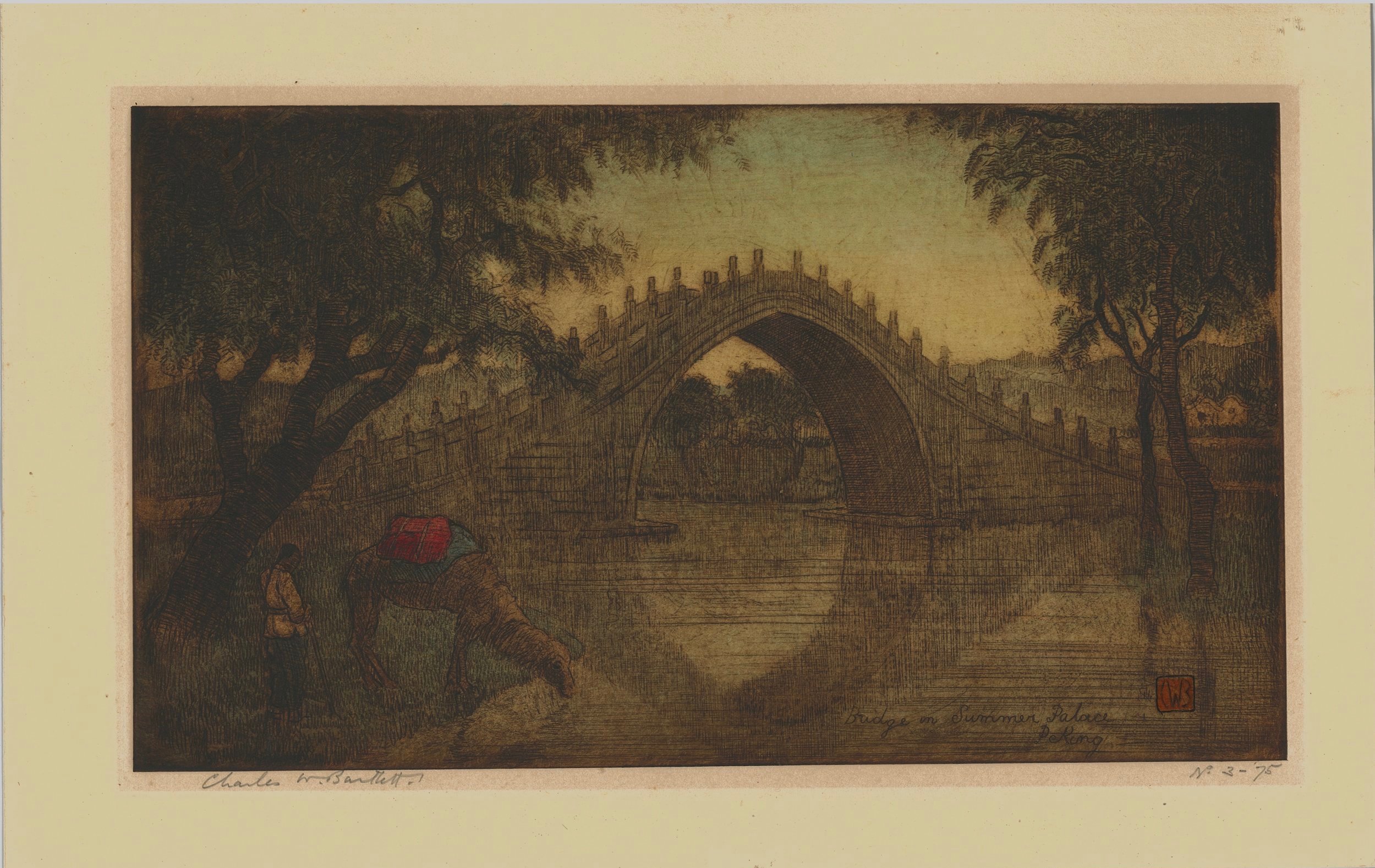

Charles W. Bartlett (1860-1940)

Talk about a fascinating life.

Charles William Bartlett was born in England, studied in Paris, and became a renowed watercolorist. After the tragic deaths of his wife and son, he travelled the world for two years with his second wife, ending up in Japan in 1915. Here he met Watanabe Shozaburo, who published 21 woodblocks from Bartlett's designs in 1916, including six prints of Japanese landscapes. Bartlett’s designs of India, where he’d spent time during his journey, are said to have inspired the Indian designs of Hiroshi Yoshida.

In time, Bartlett and his wife left Japan for Hawaii, where they lived permanently from then on. He returned to Japan one more time, in 1919, where he did more work with Watanabe. These included noted designs of Hawaiian surfers. Interestingly, Bartlett essentially hired Watanabe to publish his prints, instead of the other way around, and kept ownership of the blocks. They remain in Hawaii to this day.

Elizabeth Keith (1887-1956)

Elizabeth Keith was one of the rare Western artists in the Shin Hanga or “New Print” movement, and one of even fewer women. Her designs were clean and elegant, with a subtle pallette, and found considerable popularity in Europe at a time when the Western world was fascinated by Asia and all-things-Japan.

Born in Scotland, she first travelled to Japan when she was 28 and stayed for nine years, beginning her career as a professional artists by exhibting her watercolors. But Japan was merely her home base: she travelled often to China and Korea, countries for whom she seemed to have a strong affinity, and it is the designs she created depicting those countries that are her most renowned today.

Interestingly, they were never produced in great numbers, and are thus quite expensive and sought-after.

Bannai Kokan (1900-1962)

Born in Fukushima prefecture in 1900, Kokan studied Japanese-style painting with Bannai Seiran, eventually pivoting to Shin Hanga prints. He began but never completed a series of prints of the Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido in in the early 1930s.