Other Ukiyo-e Artists: Edo (1600–1868)

Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769-1825)

The son of a dollmaker in Edo’s shiba district, Toyokuni was the first in a truly remarkable Ukiyoe lineage, with his designs and those of his students dominating the Utagawa school — and thus, the market for Japanese woodblock prints — for decades. His long list of students would eventually include Kunisada and Kuniyoshi.

His first works, as with so many artists in Japan, were illustrations in books, but he quickly demonstrated mastery of the bijin, or beautiful woman, print.

The leaders in this field were Utamaro and Kiyonaga, but soon after Toyokuni’s first bijin prints appeared in the 1790s, he’d developed his own style. Hollis Goodall, in Living for the Moment: Japanese Prints from the Barbara S. Bowman Collection, writes “he explored a less exaggerated figure length than those of Utamaro’s beauties, still longer and more robust than those of Kiyonaga, but showing greater angularity in pose and outline.”

In the end, Toyokuni produced 90 series and many hundreds more single-sheet designs. In his 30-year career he worked for more than 100 publishers, and also produced several paintings. His works live on, but perhaps even more so do the works of those he taught and encouraged.

Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815)

Torii Kiyonaga began his training under Torii Kiyomitsu in 1765 at the age of 14 years old. Kiyonaga is considered one of the great masters of the full-color nishiki-e print and of bijin-ga, images of courtesans and other beautiful women. Like most ukiyo-e artists, however, he also produced a number of prints and paintings depicting Kabuki actors and related subjects, many of them promotional materials for the theaters. He also produced a number of shunga, or erotic images, including two adaptations of Harunobo's Zashiki Hakkei.

Chobunsai Eishi (1756-1829)

The women are beautiful, so very beautiful, and as the years went on they got taller and thinner and more elegant. Indeed, they hardly looked of this world.

They were the ever-lengthening visions of Chobunsai Eishi, seen by many as a rival to Utamaro and Kiyonaga. But truly, he was his own man, and his story is quite unusual in the annals of Ukiyoe lives.

Also known by the given name Hosoda, Eishi’s life and career took a circular journey. He was born in 1756 into a high-ranking samurai family — so high-ranking in fact, that he himself received an annual salary of 500 koku a year. (A koku was cost of rice for one man for one year, and was the main monatory measurement of Edo times.) This meant he was quite wealthy, at least by the standards of Japanese woodblock print designers; so many Ukiyoe artists, despite the fame granted them by posterity, were quite poor throughout their lives.

Eishi held a position in the Shogun Tokugawa Leheru’s palace, but gave it up to pursue painting in the Kano school. His first known prints date from 1785, and a few years later he left the Shogunate to pursue art full time. He became known for his prints of beautiful women — bijin — and was soon as equally renowned as his rivals, Utamaro and Kiyonaga. His first known designs featured courtersans, usually standing, and later he focused more on the daily routines of women, often seated, from other walks of life.

As the years progressed, his women became taller and thinner and always standing — more stereotypical examples of the ideal of female beauty than realistic depictions of it. (Edo people were actually somewhat short and compact.) As they grew upwards, the women’s necks lengthened and their heads got smaller and smaller, as least relative to their willowy bodies. They backgrounds tended to be spare, with a muted palette, quietly emphasizing the figures at the forefront of the designs.

Eishi eventually returned to his first love, painting, and by the end of his career focused on it. His paintings became sought after in the Shogun’s court. And so he once again returned to that storied world. In 1800 the Empress acquired one of his paintings, and from 1801 he dedicated himself to painting full-time.

As I said, full circle.

He died in 1829.

Keisai Eisen (1790–1848)

Playright. Student painter. Face powder salesman. Bon Vivant. Brothel owner.

Born in 1790, Keisai Eisen lived 58 years, but in those decades inhabited many lives. Naturally, he is remembered most as an artist of the Floating World, with a specialty of portraying beautiful women, but with an undeniable talent at landscapes. He was born in Edo, the son of a noted calligrapher. After the death of his father he studied under Kikugawa Eizan. His initial works reflected the influence of his mentor, but he soon developed his own style after making a living in several other realms.

He also developed a talent for privately-printed, small-scale surimono prints. His most famous landscape series was the The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaido, a project that he began but which was completed by Hiroshige, his junior, after his own work habits became erratic. His bijin-ga appeared more worldly and sensuous than those drawn by his predecessors, who had perhaps imbued them with too much stuffy elegance. Not Eisen’s. He died in 1848.

Kikukawa Eizan (1787-1867)

Kikugawa Eizan can be considered the true heir to Utamaro, even if he never studied with that legendary master of beauties.

But history records he was deeply enamored of Utamaro’s work, and when Utamaro died, it was Eizan, and not one of Utamaro’s students, who truly filled the void. His bijin-ga prints paid hommage to the master’s style, especially their poses, but their narrow faces and slim bodies were perfected by Eizan. The kimonos in which he dressed his women were often quite intricate, as were their hairstyles, with both providing fascinating and useful glimpses of the styles in the ever-stylish Edo of the time.

Eizan was born to a painter, and in the end of his life it was apparently painting that warmed his passion most. He abruptly stopped designing prints around 1830, when he was 43, but kept painting for the rest of his life. He died at 81 in 1867.

Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-1880)

The earliest known prints attributed to Utagawa Kunisada II, signed as "Kunimasa III," date from 1844. He changed his name after he married the daughter of his master, Utagawa Kunisada, who adopted him. (Her name was Osuzu, if you were wondering.)

He mimicked his master’s style, and, while never quite achieving the elder Kunisada’s stylistic heights or remarkable productivity, he did complete numerous wonderful designs, including many depicting the Tale of Genji. He became Toyokuni IV after Kunisada’s death, although history doesn’t seem to remember him with that name.

Utagawa Hirokage (active 1855–1865)

Humor has always had a place in Ukiyoe. It can be subtle, like a peek at a brothel customer’s pipe in an Eisen. Not-so-subtle, like a human head made out of naked bodies drawn by Kuniyoshi. Or really really not subtle at all, like the size of certain body parts in shunga that are, how shall we say, somewhat exaggerated.

But for a real feast of Edo-era laughs, nothing beats Utagawa Hirokage’s Comical Views of Famous Scenes of Edo from 1859. The second most well-known student of Hiroshige, the other being Shigenobu, or Hiroshige II, the details of Hirokage’s life are scarce, but this series is something to see. It is both a homage to, and a satire of, Hiroshige’s 100 Famous Views of Edo.

The backgrounds evoke the master, and we recongize many famous places. But in the foreground, all manner of mayhem unfolds. Workers tumble off the top of scaffolds. Lords emit foul bodily odors. Nasty badgers put villagers into a trance and march them through a field. It’s all pretty crazy.

Alas, not all the humor holds up well today, especially in those prints that suggest the subjects suffered serious injuries. But many of the designs have stood the test of time.

Utagawa Sadatora (active 1820s-1830s)

Utagawa Toyokuni II (Toyoshige) (1777-1835)

Toyoshige was born in 1777 and not a great deal is known about him, but he did cause something of a scandal in the Utagawa school. He stole a name, or so the legend goes.

He joined Toyokuni’s studio at age 1818, and had a specialty in actor prints and surimono, although his output was low. He was adopted by the master in 1824. But a year later the master died, and that’s where the trouble began.

Toyoshige became Toyokuni II. But did the first Toyokuni bestow the name on him, or did he just take it for himself? No one knows. But Toyokuni’s most famous and successful student, Kunisada, was reportedly quite angry that he had to be Toyokuni III. But it was what it was.

Toyoshige was a perfectly competent print designer. But there is another interesting twist to his story. He completed only one series of landscapes – “Eight Famous Views of Kanagawa.” (I have also seen it listed as “Eight Famous Views” or “Eight Famous Views of Shrines.”) It is a masterpiece, a remarkable set of prints. Bold, with extraordinarily modern designs, it was published in the 1830s just as Hokusai and Hiroshige (also a member of the Utagawa school) were making landscapes popular.

The prints in this series are filled with wonderful touches. In “Wild Geese in Miho,” for example, he creates a magnificent and towering Mount Fuji – by not showing the top of Fuji; instead, the snowy summit mixes with the clouds, but in our mind’s eye we see it. In “Night Rain at Oyama” slashing diagonal rain slices a mountain into pieces. Extraordinary.

Toyoshige (Toyokuni II) died soon after, in 1835, leaving us the mystery of why he only created one series of landscapes, but grateful that he did.

Katsukawa Shunzan (active about 1781–1801)

Katsukawa Shunsho ( 1726–1792)

Katsukawa Shuncho (1750–1821)

Katsukawa Shunsho may not be the most well-known name in Ukiyoe, but his impact on the form and its history are immeasurable. He is credited with inventing the genre of actor portrait prints, and his students included none other than Katsushika Hokusai, who probably is the most well-known Japanese woodblock print artist in history.

Born in 1726 at the dawn of the Ukiyoe era, Shunsho initially studied with the Torii school, but soon broke away to form his own school, one that would eventually carry his name.

He invented the idea of Kabuki actor portraits that actually looked like the actors they were depicting. He also produced the first “big head” full-face images. And he showed actors (and all were men, at the time) in their dressing rooms. This was revolutionary because, up until this point, print artists had portrayed the roles played by actors, but not the individual thespians themselves. The ravenous theater-going public ate them up, and a 100-year craze was born.

This is not to discount Shunsho’s portraits of beautiful women (bijin). His were lovely, indeed, and sought after. But for the most part they were paintings, not prints. He only produced a handful of prints of women. He died in 1793.

Utagawa Yoshifuji (1828 - 1887)

Utagawa Yoshifuji had talent but lived in the wrong era. He was born in 1828 and became a student of the great Utagawa Kuniyoshi, but by the time he died in 1887, Ukiyoe was in decline. While there was still some great work being produced in those waning days of Japanese woodblock prints, the competition was tougher, the audience smaller.

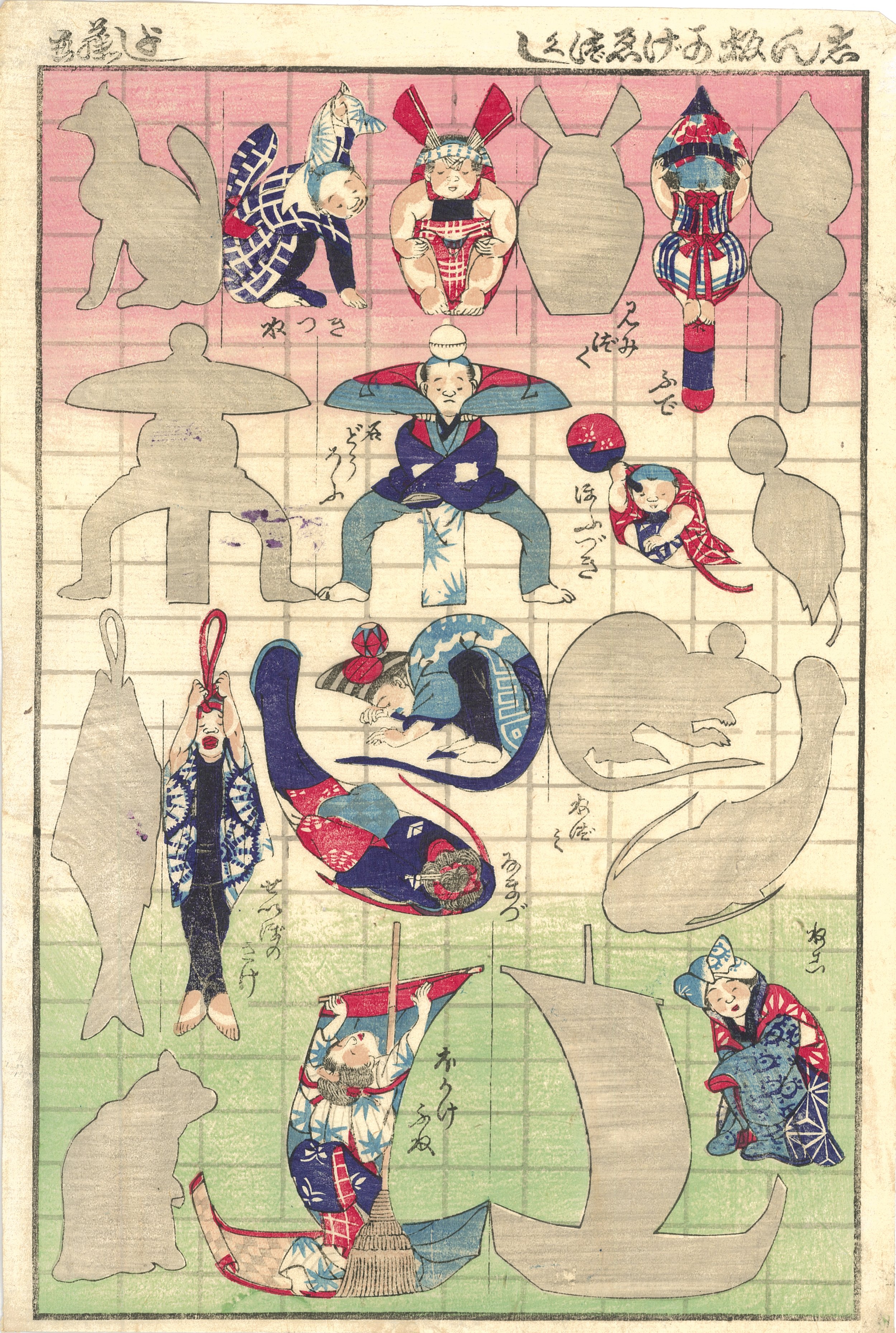

Yoshifuji’s output touched on all the major themes of these years – warriors, Yokohama-e, bijin. This fan print of two young women writing down their wishes and attaching them to bamboo stalks for the Tanabata Festival is undeniably lovely. But in the end, Yoshifuji’s legacy was in omocha-e, or paintings of toys. This even earned him the nickname, Omocha Yoshifuji. He also illustrated children's books.

What could he do? He had to make a living using skills that were fast passing from popular favor. So: prints for children it was.

The scholar Rebecca Salter points out that these children’s prints were not without merit, even if serious collectors may have scoffed:

“The standard of production was undeniably inferior to earlier prints, but this does not mean that these prints are not worthy of attention,” she wrote. “They may have been made as throwaway items (and indeed few remain) but they demonstrate a visual sophistication reminiscent of earlier prints and can reveal subtle insights into the forces working to change Japanese society from within and without.”

Kubo Shunman (1757-1820)

Kubo Shunman, if the works he left behind are any indication, was a painter first, and a printmaker second. After his death in 1820, he left us 70 paintings, making him the most prolific artist of the Kitao school. His prints, on the other hand, were few and far between, but they had an elegance befitting a man who had been a student of the great Torii Kiyonaga.

Shunman studied with the painters Kitao Shigemasa and Kaatori Uohiko. But he also studied with the poet Katori Nahiko, for this young talent was also a poet of note.

His prints often featured beautiful women, always slender, well-coiffed and sumptuously dressed. The scholar Andres Marks notes that these women were often set in landscapes, such as in Shunman’s most famous woodblock print, a five-sheet work entitled “Six Jewel Rivers.” These works stand along as single sheets – such as this one – but can naturally be combined.

He embraced a quiet palette. In fact, he was part of the beni-girai or “red-hating” school, meaning that he eschewed this particular pigment, finding it garish. The phrase directly translates as “dislike of red.”

Later in life, he combined his poetry and his printmaking in designs that featured verse. Like many other Ukiyoe artists, he was also known to produce erotic prints, shunga, to make ends meet.

Unlike many Ukiyoe artists, he also was adept at still life. These were often featured in his small surimono private prints. In fact, Marks notes, Shunman’s earliest known work was a copy of a votive plaque by Nahiko in 1774. Interestingly, but likely little more than a coincidence, at this exact same time on the other side of the planet in France, Jean Siméon Chardin, perhaps history’s greatest still life painter, was at the height of his powers.

Small world. But then again, isn’t that what still life paintings are all about?

Bunro (Active early 1800’s)

Kawanabe Kyosai(1831-1889)

Kawanabe Kyosai was a caricaturist at a time when Japan was going through a momentous shift, one unprecedented in human history, metamorphosing at breakneck pace from a feudal society to a modern nation.

He lived from 1831 to 1889, he studied painting and drawing, and was briefly a student of Kuniyoshi. But he will be remembered mostly within the political milieu, exaggerating human features and scenes, and often depicting events without actually depicting them.

For example, during the Satsuma Rebellion in the 1870s, in which samurai rebels fought the new Meiji government, he illustrated those battles in extreme detail, with one change from reality – the warring soldiers were all frogs.

His prints have a loose, frantic quality, as if they were dashed off in a rush before the authorities knocked on the door. They are filled with manic energy – indeed mayhem burst forth from the page even more maniacally than in the designs of his brief master, Kuniyoshi, or Kuniyoshi’s most famous student (and Kyosai’s contemporary), Yoshitoshi.

But it was hard to typecast him. He also produced paintings with an almost classic quality. Indeed, the wildly varying types of work he produced resulted in him being a lesser-known Ukiyoe light, despite his remarkable ability. But that seems to be changing.

Kitagawa Shikimaro (dates unknown)

Shotei Hokuju (1763–1824)

Was Shotei Hokuju, perhaps Hokusai’s most famous student, the stylistic father of… Pablo Picasso?

Not really, but in the uniquely conjured works of this, perhaps Ukiyoe’s first great landscape artist, we see many hints of modern art. We glimpse a kind of cubism and an almost abstract approach to the land and the humans who live within it. We also see perspective, shadows and billowing clouds. They suggest a fertile artistic mind striving for something new. And all this is the early mid-period of Ukiyoe.

Hokuju is believed to have been born in 1763, and joined Hokusai’s studio around 1793. His most famous works – including “True Depiction of the Monkey Bridge In Kay Province” – predated the master’s most notable designs, though of course they never garnered as much fame.

This print includes Western-style clouds, an example of Hokuju experimenting with foreign concepts. Where he saw them is hard to determine, since such artistic devices were banned in Edo-period Japan, and one suspects the exposure to them was fleeting, because he didn’t quite master all the techniques, such as perspective and use of vanishing points.

But these imperfections only add to the pleasure of his work, capturing the moment when someone was happily wrestling with new ideas. He was not hugely prolific: in addition to prints, almost all of them landscapes, he designed surimono and at least one illustrated book.

Shotei Hokuju died in 1824.

Katsukawa Shunsen (1762–1830)

Totoya Hokkei (1780–1850)

From fish seller to printmaker.

Totoya Hokkei was born in Akasaka in Edo to a family of fishmongers in 1780 and took up his ancestors’ trade before his obvious talents led him to study painting in the Kano School. Eventually, he left painting to pursue print-making, studying with Hokusai. In time, along with Hokuju, he’d become one of the master’s most successful and well-known students.

Hokkei’s dramatic and forceful lines echo those of Hokusai, although often on a smaller scale. That’s because Hokkei became one of the premier designers of surimono, privately produced Ukiyoe. Given as gifts on auspicious occasions, these prints’ diminutive size did not subtract from their elegant designs and often luxurious, intricate production.

Hokusai’s style is evident in many of Hokkei’s works, but nonetheless they are clearly his own. Several powerful and ominous views of Mount Fuji, for example, have strong echoes of the master. In all, Hokkei produced more than 800 surimono, many of them extraordinarily creative.

Hokkei also produced quite a few books, including sketchbooks reminiscent of Hokusai’s manga, but relatively few full-sized prints.

He died in 1850 at age 70.