Chikanobu

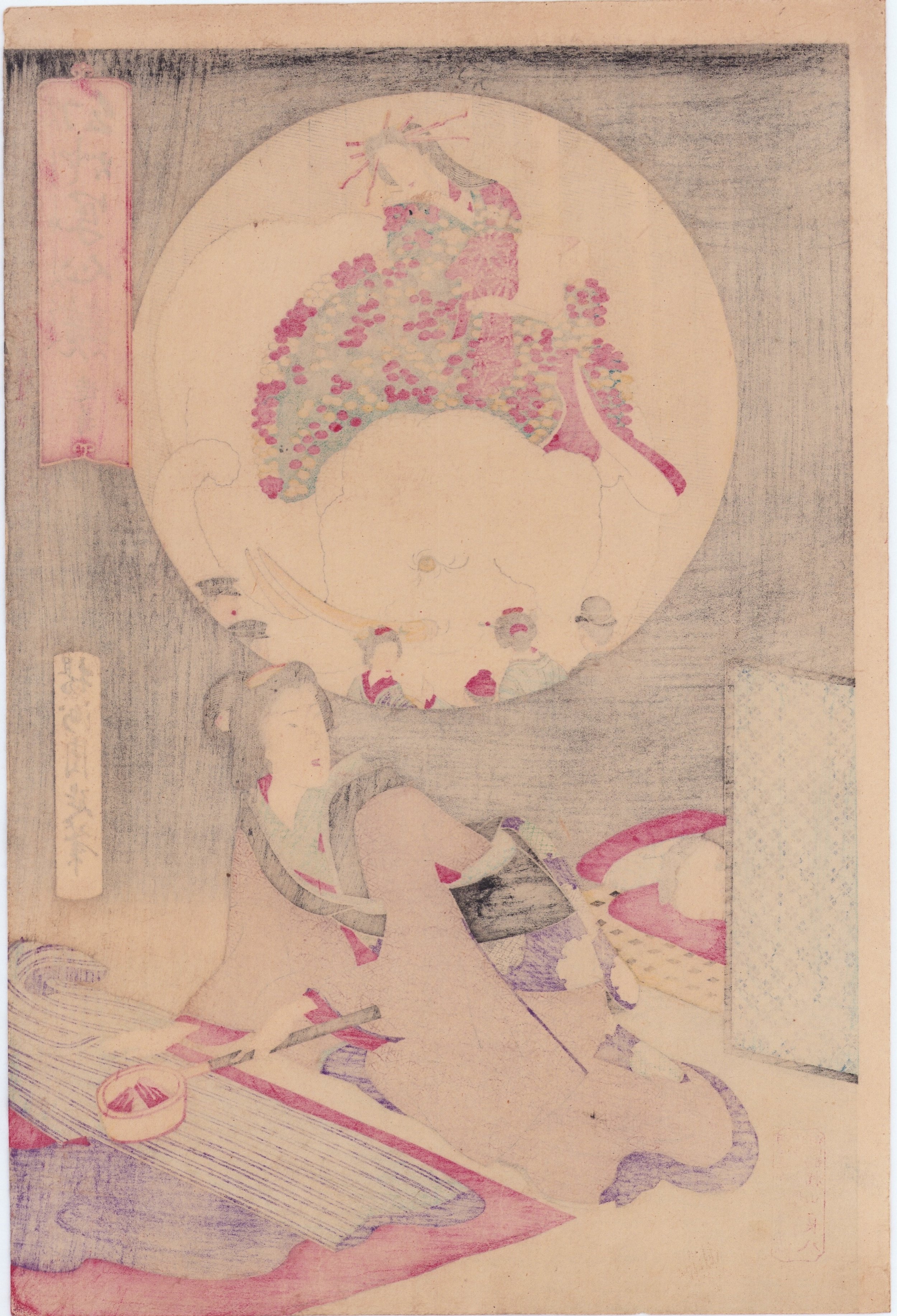

Chrysanthemun Figure, Collection of Magic Lantern

楊洲周延 Toyohara Chikanobu (1838–1912)

幻灯写心竞 造菊

Chrysanthemun Figure, from the series of Collection of Magic Lantern

1890

木版画 | 纵绘大判 | 36.6cm x 25cm

Woodblock-print | Oban-tate-e | 36.6cm x 25cm

品相非常好

Very good condition

$850

“幻灯”,即幻灯机,又称魔灯、西洋灯,一种主要由一个或数个透镜以及光源构成的投影成像设备,是现代幻灯片投影仪的原型。其诞生于17世纪初,至晚在18世纪中期即从西方引入日本,为歌舞伎等曲艺的发展起到了一定的推动作用;明治时期更是作为课堂中的教具,用以展现西方的社会万象与先进技术。

如满月的幻灯圆光内,承载着“文明开化”大时代背景下一位位女性的憧憬与梦想。跪坐于地的年轻母亲正手持火熨斗熨平衣装,身侧的孩子已在屏风后安然睡熟。望着烧得通红的炭火,心事慢慢浮现:“多想去看一场盛大的菊人形展会啊!”在巨大圣洁的金牙白象背上,一朵朵红菊黄菊叠砌而成的美艳花魁浅笑骑坐。无论是打扮西化的男人,还是一身和服的女子,无不为之而倾倒,连连发出赞叹。幻想着、幻想着,手中的活儿也并没有停下。梦与现实,共竞成画。

作为周延的晚期成熟作品,本作摺印技法极为考究:和服的玄色腰带,与手持火熨斗的斗柄皆由漆绘装饰而成,成本高昂,光气内敛;白象的庞大身躯则是以空摺技法拓印,看似无色,实则触之凹凸,使人顿觉花团锦簇。

The Magic Lantern – also known as a “Slide Lantern” -- was an early projection device that illuminated interchangeable slides within a wooden box. A precursor to the slide projector, as well as movies, it was a hit in Meiji Japan, as were so many items that flooded the country after it was “opened” for trade with the West. Anyone could look in and glimpse distant and amazing worlds and events, one after the other. It was a dream machine.

And like many curious Western devices, it began popping up in woodblock prints. Toyohara Chikanobu used it as the centerpiece and narrative conceit of one of his most interesting series, Collection of Magic Lantern. Here he took the dream-like quality of these photographic images to represent actual dreams and daydreams. But not just any dreams: these images represented the hopes and ambitions -- some modest, some truly bold -- of Japanese women.

This was a time when society norms were slowly changing in Japan as the details of other cultures became known. Among the shifting views was that of a woman’s role in society. To be sure, change came slowly, and still does, but Chikanobu did something extraordinary here. While female beauty had long been an Ukiyoe staple, women had usually been treated as little more than pretty dolls or sexual playthings. Not here. Here the artist gives women hopes and dreams equaling, even rivalling, those of men.

Each of the prints from this series is filled with visual clues, some of which are hard to divine. In this print, a woman – a wife and mother, we assume – uses an old-fashioned, coal-heated iron to smooth her husband’s kimono, while her child sleeps nearby. It is a scene of domestic bliss, and it is wonderfully drawn (love the iron). But her mind is elsewhere, and her thoughts are captured in the circular image above her head, the Magic Lantern of her day (or evening) dream.

And what is it? Well, she appears to want to ride an elephant while oddly miniature people gather around her. I’ve Googled “What does it mean if I dream of riding an elephant amid tiny people?” but haven’t found any satisfying explanations, so let’s just assume that elephants were rarely if ever seen in Meiji Japan, so riding one would represent a dramatic break from the daily routine of ironing your husband’s kimono.

The colors are luxurious, all glowing reds and purple with a gorgeous almost-magenta bokashi wash in the background, and the intricate printing is remarkably precise, as befitting the high craftsmanship marking the final days of classic woodblock printing in Japan. The circle encompassing the dream/wish is a strong and inviting graphic element.

Other examples of this series display aspirations both mundane and extraordinary.

In this one, a classic Sumida River snow scene is juxtaposed with a woman reading a newspaper, suggesting she’s following current events. In another, a woman in Western dress and carrying a heavy, cloth-bound book dreams of giving a speech at what appears to be a political rally. Maybe it’s more than a dream: maybe it’s her plan. I can’t find a good link to this print, but the idea must have been shocking at the time – a woman running for elected office?

One wonders: was he joking? Was he making fun of his subjects for the amusement of the mostly male print-buying public? I don’t think so: these prints show real empathy for their subjects, in my opinion.

I go back-and-forth on Chikanobu, who some consider the last true Ukiyoe print designer. (Indeed, the photographs used in the Magic Lanterns at the time were fast displacing woodblock prints.) Sometimes his images are just too pretty-pretty and decorative for me. But in this series, he broke the mold. He provided glimpses of women with three-dimensional personalities of the kind rarely seen in Ukiyoe. And they are great to look at.

Interested in purchasing?

Please contact us.

楊洲周延 Toyohara Chikanobu (1838–1912)

幻灯写心竞 造菊

Chrysanthemun Figure, from the series of Collection of Magic Lantern

1890

木版画 | 纵绘大判 | 36.6cm x 25cm

Woodblock-print | Oban-tate-e | 36.6cm x 25cm

品相非常好

Very good condition

$850

“幻灯”,即幻灯机,又称魔灯、西洋灯,一种主要由一个或数个透镜以及光源构成的投影成像设备,是现代幻灯片投影仪的原型。其诞生于17世纪初,至晚在18世纪中期即从西方引入日本,为歌舞伎等曲艺的发展起到了一定的推动作用;明治时期更是作为课堂中的教具,用以展现西方的社会万象与先进技术。

如满月的幻灯圆光内,承载着“文明开化”大时代背景下一位位女性的憧憬与梦想。跪坐于地的年轻母亲正手持火熨斗熨平衣装,身侧的孩子已在屏风后安然睡熟。望着烧得通红的炭火,心事慢慢浮现:“多想去看一场盛大的菊人形展会啊!”在巨大圣洁的金牙白象背上,一朵朵红菊黄菊叠砌而成的美艳花魁浅笑骑坐。无论是打扮西化的男人,还是一身和服的女子,无不为之而倾倒,连连发出赞叹。幻想着、幻想着,手中的活儿也并没有停下。梦与现实,共竞成画。

作为周延的晚期成熟作品,本作摺印技法极为考究:和服的玄色腰带,与手持火熨斗的斗柄皆由漆绘装饰而成,成本高昂,光气内敛;白象的庞大身躯则是以空摺技法拓印,看似无色,实则触之凹凸,使人顿觉花团锦簇。

The Magic Lantern – also known as a “Slide Lantern” -- was an early projection device that illuminated interchangeable slides within a wooden box. A precursor to the slide projector, as well as movies, it was a hit in Meiji Japan, as were so many items that flooded the country after it was “opened” for trade with the West. Anyone could look in and glimpse distant and amazing worlds and events, one after the other. It was a dream machine.

And like many curious Western devices, it began popping up in woodblock prints. Toyohara Chikanobu used it as the centerpiece and narrative conceit of one of his most interesting series, Collection of Magic Lantern. Here he took the dream-like quality of these photographic images to represent actual dreams and daydreams. But not just any dreams: these images represented the hopes and ambitions -- some modest, some truly bold -- of Japanese women.

This was a time when society norms were slowly changing in Japan as the details of other cultures became known. Among the shifting views was that of a woman’s role in society. To be sure, change came slowly, and still does, but Chikanobu did something extraordinary here. While female beauty had long been an Ukiyoe staple, women had usually been treated as little more than pretty dolls or sexual playthings. Not here. Here the artist gives women hopes and dreams equaling, even rivalling, those of men.

Each of the prints from this series is filled with visual clues, some of which are hard to divine. In this print, a woman – a wife and mother, we assume – uses an old-fashioned, coal-heated iron to smooth her husband’s kimono, while her child sleeps nearby. It is a scene of domestic bliss, and it is wonderfully drawn (love the iron). But her mind is elsewhere, and her thoughts are captured in the circular image above her head, the Magic Lantern of her day (or evening) dream.

And what is it? Well, she appears to want to ride an elephant while oddly miniature people gather around her. I’ve Googled “What does it mean if I dream of riding an elephant amid tiny people?” but haven’t found any satisfying explanations, so let’s just assume that elephants were rarely if ever seen in Meiji Japan, so riding one would represent a dramatic break from the daily routine of ironing your husband’s kimono.

The colors are luxurious, all glowing reds and purple with a gorgeous almost-magenta bokashi wash in the background, and the intricate printing is remarkably precise, as befitting the high craftsmanship marking the final days of classic woodblock printing in Japan. The circle encompassing the dream/wish is a strong and inviting graphic element.

Other examples of this series display aspirations both mundane and extraordinary.

In this one, a classic Sumida River snow scene is juxtaposed with a woman reading a newspaper, suggesting she’s following current events. In another, a woman in Western dress and carrying a heavy, cloth-bound book dreams of giving a speech at what appears to be a political rally. Maybe it’s more than a dream: maybe it’s her plan. I can’t find a good link to this print, but the idea must have been shocking at the time – a woman running for elected office?

One wonders: was he joking? Was he making fun of his subjects for the amusement of the mostly male print-buying public? I don’t think so: these prints show real empathy for their subjects, in my opinion.

I go back-and-forth on Chikanobu, who some consider the last true Ukiyoe print designer. (Indeed, the photographs used in the Magic Lanterns at the time were fast displacing woodblock prints.) Sometimes his images are just too pretty-pretty and decorative for me. But in this series, he broke the mold. He provided glimpses of women with three-dimensional personalities of the kind rarely seen in Ukiyoe. And they are great to look at.

Interested in purchasing?

Please contact us.

楊洲周延 Toyohara Chikanobu (1838–1912)

幻灯写心竞 造菊

Chrysanthemun Figure, from the series of Collection of Magic Lantern

1890

木版画 | 纵绘大判 | 36.6cm x 25cm

Woodblock-print | Oban-tate-e | 36.6cm x 25cm

品相非常好

Very good condition

$850

“幻灯”,即幻灯机,又称魔灯、西洋灯,一种主要由一个或数个透镜以及光源构成的投影成像设备,是现代幻灯片投影仪的原型。其诞生于17世纪初,至晚在18世纪中期即从西方引入日本,为歌舞伎等曲艺的发展起到了一定的推动作用;明治时期更是作为课堂中的教具,用以展现西方的社会万象与先进技术。

如满月的幻灯圆光内,承载着“文明开化”大时代背景下一位位女性的憧憬与梦想。跪坐于地的年轻母亲正手持火熨斗熨平衣装,身侧的孩子已在屏风后安然睡熟。望着烧得通红的炭火,心事慢慢浮现:“多想去看一场盛大的菊人形展会啊!”在巨大圣洁的金牙白象背上,一朵朵红菊黄菊叠砌而成的美艳花魁浅笑骑坐。无论是打扮西化的男人,还是一身和服的女子,无不为之而倾倒,连连发出赞叹。幻想着、幻想着,手中的活儿也并没有停下。梦与现实,共竞成画。

作为周延的晚期成熟作品,本作摺印技法极为考究:和服的玄色腰带,与手持火熨斗的斗柄皆由漆绘装饰而成,成本高昂,光气内敛;白象的庞大身躯则是以空摺技法拓印,看似无色,实则触之凹凸,使人顿觉花团锦簇。

The Magic Lantern – also known as a “Slide Lantern” -- was an early projection device that illuminated interchangeable slides within a wooden box. A precursor to the slide projector, as well as movies, it was a hit in Meiji Japan, as were so many items that flooded the country after it was “opened” for trade with the West. Anyone could look in and glimpse distant and amazing worlds and events, one after the other. It was a dream machine.

And like many curious Western devices, it began popping up in woodblock prints. Toyohara Chikanobu used it as the centerpiece and narrative conceit of one of his most interesting series, Collection of Magic Lantern. Here he took the dream-like quality of these photographic images to represent actual dreams and daydreams. But not just any dreams: these images represented the hopes and ambitions -- some modest, some truly bold -- of Japanese women.

This was a time when society norms were slowly changing in Japan as the details of other cultures became known. Among the shifting views was that of a woman’s role in society. To be sure, change came slowly, and still does, but Chikanobu did something extraordinary here. While female beauty had long been an Ukiyoe staple, women had usually been treated as little more than pretty dolls or sexual playthings. Not here. Here the artist gives women hopes and dreams equaling, even rivalling, those of men.

Each of the prints from this series is filled with visual clues, some of which are hard to divine. In this print, a woman – a wife and mother, we assume – uses an old-fashioned, coal-heated iron to smooth her husband’s kimono, while her child sleeps nearby. It is a scene of domestic bliss, and it is wonderfully drawn (love the iron). But her mind is elsewhere, and her thoughts are captured in the circular image above her head, the Magic Lantern of her day (or evening) dream.

And what is it? Well, she appears to want to ride an elephant while oddly miniature people gather around her. I’ve Googled “What does it mean if I dream of riding an elephant amid tiny people?” but haven’t found any satisfying explanations, so let’s just assume that elephants were rarely if ever seen in Meiji Japan, so riding one would represent a dramatic break from the daily routine of ironing your husband’s kimono.

The colors are luxurious, all glowing reds and purple with a gorgeous almost-magenta bokashi wash in the background, and the intricate printing is remarkably precise, as befitting the high craftsmanship marking the final days of classic woodblock printing in Japan. The circle encompassing the dream/wish is a strong and inviting graphic element.

Other examples of this series display aspirations both mundane and extraordinary.

In this one, a classic Sumida River snow scene is juxtaposed with a woman reading a newspaper, suggesting she’s following current events. In another, a woman in Western dress and carrying a heavy, cloth-bound book dreams of giving a speech at what appears to be a political rally. Maybe it’s more than a dream: maybe it’s her plan. I can’t find a good link to this print, but the idea must have been shocking at the time – a woman running for elected office?

One wonders: was he joking? Was he making fun of his subjects for the amusement of the mostly male print-buying public? I don’t think so: these prints show real empathy for their subjects, in my opinion.

I go back-and-forth on Chikanobu, who some consider the last true Ukiyoe print designer. (Indeed, the photographs used in the Magic Lanterns at the time were fast displacing woodblock prints.) Sometimes his images are just too pretty-pretty and decorative for me. But in this series, he broke the mold. He provided glimpses of women with three-dimensional personalities of the kind rarely seen in Ukiyoe. And they are great to look at.

Interested in purchasing?

Please contact us.

Toyohara Chikanobu (1838–1912)

Toyohara Chikanobu was born in 1838 in Edo and, obviously possessing talent, studied the Kanō school of painting. But his love was Ukiyoe. He studied with Kuniyoshi and, upon the master’s death, with Kunichika.

A samurai like his father, Chikanobu fought on the side of the Shogan against the Emperor Meiji as Japan moved unsteadily towards modernity, and was arrested when the Emperor’s forces triumphed. But by the 1880s he was free to pursue his art.

His work ranged from Japanese mythology to battles to women's fashions. A great many were triptychs, and some were quite garish in their choice of colors, as was the style in the waning days of Ukiyoe. His designs illustrating women’s fashion were especially interesting because they depicted the radical shift from traditional to Western clothing during the Meiji restoration and the changes in coiffures and make-up styles that accompanied them. When he drew women in traditional dress, it was a nod to the recent past, with a healthy dose of nostalgia. He died in 1912.