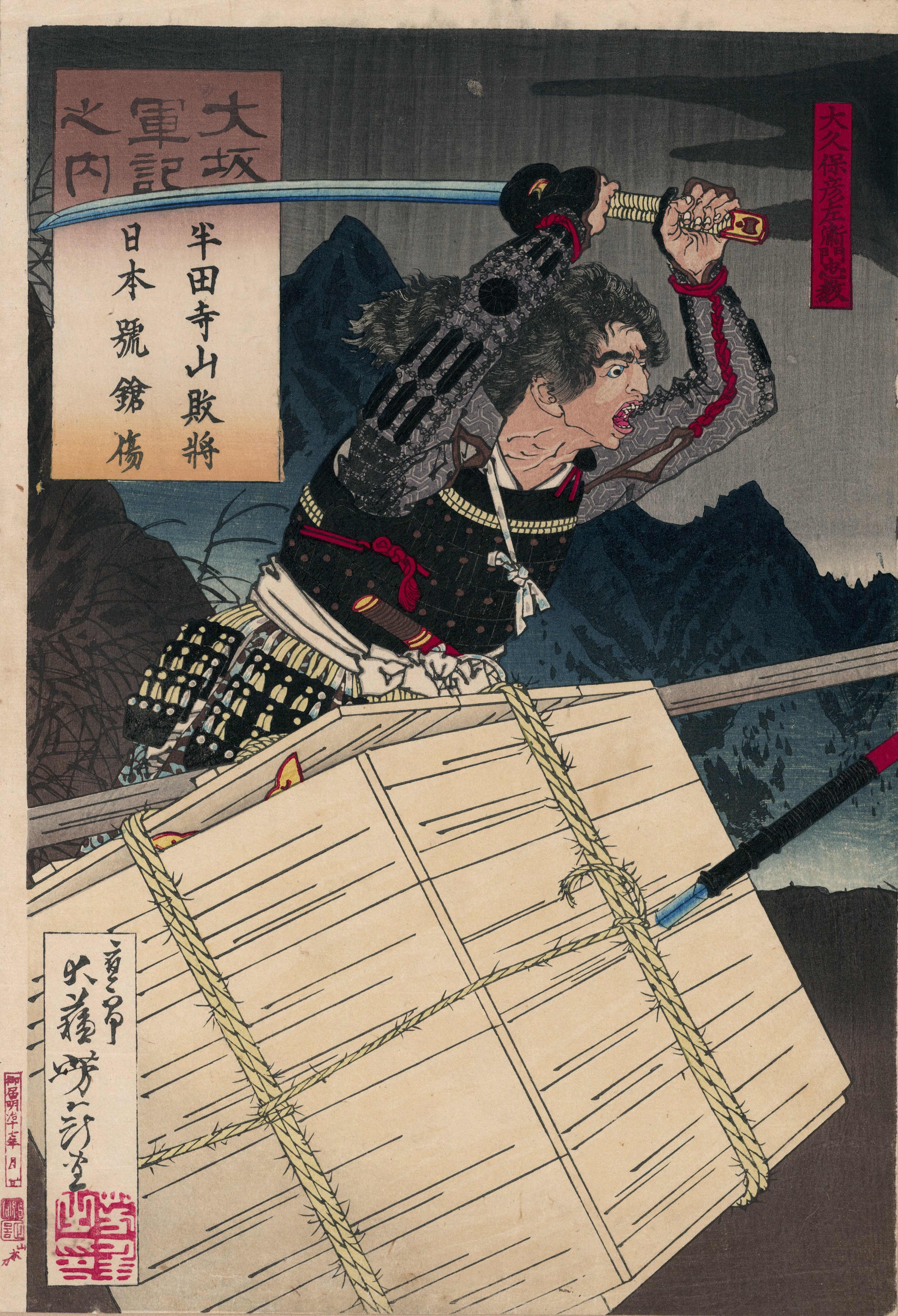

Yoshitoshi | Okuko Hikozaemon Protects the Tokugawa Shogun

月岡芳年 Tsukioka Yoshitoshi(1839–1892)

大坂軍記之内 半田寺山敗将日本號鎗傷

Okuko Hikozaemon Protects the Tokugawa Shogun from the Spear of Goro Matabei Mototsugu, from the series of The Siege of Osaka

1884

木版画|三幅续绘-纵绘大判|37cm × 25cm × 3

Woodblock|Triptych-Oban-tate-e|37cm × 25cm × 3

早期版次;颜色鲜艳;品相非常好

Fine impression, color and condition

$4,600

冷月如钩,黑云四散,松风簌簌,四百年前的某个夜里,一位身背襁褓的武士在已放倒多名敌人后丝毫不惧面前气势汹汹、挥刀而来的对手,提起手中的名枪“日本号”便向身前的驾笼奋力刺去;而在那驾笼之中躲藏着的,便是一代枭雄德川家康(1543-1616)。

以上的描述,便是对本作的精炼写照。画面中央那位手持名枪“日本号”的武士,即丰臣家的家臣后藤基次(1560-1615),在他肩头面露惧色的孩子,则是丰臣秀赖之子国松。与之相对的画面左部,高举长刀、放声大喊预备劈砍而来的德川家武士名为大久保忠教(1560-1639),一看便是要竭尽全力保卫住藏在驾笼中的自家主公。芳年以其独特的暴力美学,描绘了一幅传统演义中的经典场面,无论是电影感十足的构图,还是简练又不失细腻的画风,都能让观者大呼过瘾。

Interested in purchasing?

Please contact us.

月岡芳年 Tsukioka Yoshitoshi(1839–1892)

大坂軍記之内 半田寺山敗将日本號鎗傷

Okuko Hikozaemon Protects the Tokugawa Shogun from the Spear of Goro Matabei Mototsugu, from the series of The Siege of Osaka

1884

木版画|三幅续绘-纵绘大判|37cm × 25cm × 3

Woodblock|Triptych-Oban-tate-e|37cm × 25cm × 3

早期版次;颜色鲜艳;品相非常好

Fine impression, color and condition

$4,600

冷月如钩,黑云四散,松风簌簌,四百年前的某个夜里,一位身背襁褓的武士在已放倒多名敌人后丝毫不惧面前气势汹汹、挥刀而来的对手,提起手中的名枪“日本号”便向身前的驾笼奋力刺去;而在那驾笼之中躲藏着的,便是一代枭雄德川家康(1543-1616)。

以上的描述,便是对本作的精炼写照。画面中央那位手持名枪“日本号”的武士,即丰臣家的家臣后藤基次(1560-1615),在他肩头面露惧色的孩子,则是丰臣秀赖之子国松。与之相对的画面左部,高举长刀、放声大喊预备劈砍而来的德川家武士名为大久保忠教(1560-1639),一看便是要竭尽全力保卫住藏在驾笼中的自家主公。芳年以其独特的暴力美学,描绘了一幅传统演义中的经典场面,无论是电影感十足的构图,还是简练又不失细腻的画风,都能让观者大呼过瘾。

Interested in purchasing?

Please contact us.

月岡芳年 Tsukioka Yoshitoshi(1839–1892)

大坂軍記之内 半田寺山敗将日本號鎗傷

Okuko Hikozaemon Protects the Tokugawa Shogun from the Spear of Goro Matabei Mototsugu, from the series of The Siege of Osaka

1884

木版画|三幅续绘-纵绘大判|37cm × 25cm × 3

Woodblock|Triptych-Oban-tate-e|37cm × 25cm × 3

早期版次;颜色鲜艳;品相非常好

Fine impression, color and condition

$4,600

冷月如钩,黑云四散,松风簌簌,四百年前的某个夜里,一位身背襁褓的武士在已放倒多名敌人后丝毫不惧面前气势汹汹、挥刀而来的对手,提起手中的名枪“日本号”便向身前的驾笼奋力刺去;而在那驾笼之中躲藏着的,便是一代枭雄德川家康(1543-1616)。

以上的描述,便是对本作的精炼写照。画面中央那位手持名枪“日本号”的武士,即丰臣家的家臣后藤基次(1560-1615),在他肩头面露惧色的孩子,则是丰臣秀赖之子国松。与之相对的画面左部,高举长刀、放声大喊预备劈砍而来的德川家武士名为大久保忠教(1560-1639),一看便是要竭尽全力保卫住藏在驾笼中的自家主公。芳年以其独特的暴力美学,描绘了一幅传统演义中的经典场面,无论是电影感十足的构图,还是简练又不失细腻的画风,都能让观者大呼过瘾。

Interested in purchasing?

Please contact us.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839–1892)

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi may have lived for only 53 years, a short lifespan even in Edo times, but the history he witnessed and the myriad styles he embraced could have easily filled twice that many decades. Beginning as a more-or-less classic Ukiyo-e artist of the Utagawa school, in the waning days of the Shogunate, he developed a style that was both in-sync with Western styles and utterly his own. He was there as Japan metamorphized from a feudal land to a nascent modern society, and he managed to capture that elusive moment in time in more than 2000 woodblock prints for more than 50 publishers.

You could say he was the last great Ukiyo-e artist, and perhaps the first great post-Ukiyo-e artist. His fantastical designs ranged from history – often with buckets of blood – to bijin (beautiful women) to landscapes. He depicted people from a variety of angles and gave them intricate, and often grotesque, facial characteristics, a far cry from the simple, stereotypical visages common to Japanese woodblock prints. And he could have fun. One of his last great series, 1888’s “32 Aspects of Women,” humorously shows women through various realms of Japanese culture, and depicts very specifics moods and sensations – for example, “Cool,” “Thirsty” and “Itchy.” My favorite? “Disagreeable: Habits of a young woman of Nagoya in the Ansei era.” Ha! What a pill she looks like.

Yoshitoshi was born into a merchant family in 1839. He was an early student of Kuniyoshi, who gave him his name. Many of his warrior designs, especially the earlier ones, show a clear debt to the master, with all manner of high energy action filling his oban-size prints. He became known as a “war artist” specializing in bloody designs in the 1860s. He did numerous warrior, folklore and history series’ during this period.

But those were not his only genres. He also contributed to the epic “Processional Tokaido,” in which most of the great Ukiyo-e artists and publishers of the time combined forces to depict the Shogun’s journey to Kyoto to pay respects to the Emperor, and did his share of “Yokohama-e,” prints depicting the newly arrived Westerners.

He was tormented by a mysterious mental disorder – some say that’s what sparked such a violent imagination – and had numerous marriages and amorous affairs. He stopped working for a period, and when he came back called himself Taiso – resurrection. By the 1880’s his talent reached it’s zenith, with his epic “100 Aspects of the Moon,” and other series. His drawings and color schemes became more elaborate and more, well, his. They switched easily between bold and blunt and delicate and sensitive (and back again). Still suffering from mental illness, he died in 1892.

Partial citation: Marks, Andreas, Japanese Woodblock Prints, Artists, Publishers and Masterworks (Tuttle; 2010).